President Donald Trump said Wednesday that he will impose a new 10 percent tariff on all imported goods along with higher import taxes tailored for each of about 60 countries that his advisers say maintain the largest barriers against U.S. products, in a sharp turn toward the kind of protectionism that the United States abandoned nearly a century ago.

To impose the new tariffs, the president declared a national emergency, citing the annual merchandise trade deficit that the United States has run each year since 1975.

“For decades, our country has been looted, pillaged, raped and plundered by nations near and far, both friend and foe alike,” Trump said. “But it is not going to happen anymore.”

The tariff increases that the president announced had little modern precedent and would erect towering impediments to products from dozens of foreign countries, many of them poor nations that embraced exporting as a tool to escape grinding poverty.

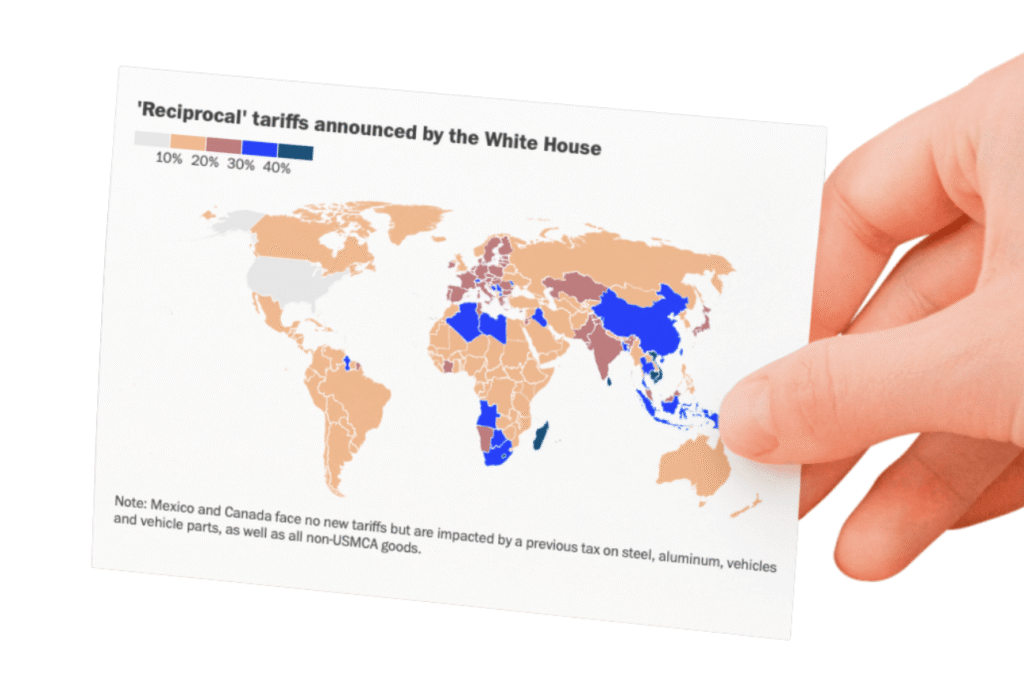

American importers, for example, will pay an additional 34 percent tariff on products from China, some of which already face 45 percent fees. Vietnam, which the administration says has become a transshipment point for Chinese companies seeking to dodge U.S. tariffs, will see its goods hit with a new 46 percent tariff. Cambodian goods, likewise, will be charged an additional 49 percent levy.

Canada and Mexico, at least for now, face no new trade penalties.

‘Reciprocal’ tariffs announced by the White House

High tariffs and a range of other practices, including currency manipulation, value-added taxes, and product safety regulations explain why the United States buys so much more from the rest of the world than it sells to foreign customers, he said during a Rose Garden ceremony featuring hard-hat clad union workers, lawmakers and journalists. Erasing these persistent imbalances in global trade, which have hollowed out factory communities and weakened national defense, is now official U.S. policy, according to an executive order that the president signed on Wednesday.

Speaking in blunt, sometimes intemperate language, the president assailed the nation’s trading partners, including some of its closest allies, as “foreign cheaters” and “foreign scavengers” who had “ripped off Americans” for 50 years. Trump’s tone echoed the dark portrait of “American carnage” that he had sketched in his first inaugural address in 2017.

The early reaction from mainstream economists and business groups was grim, while industries that will enjoy new protection against foreign competition applauded. Although Trump’s announcement came after financial markets had closed, premarket trading pushed U.S. financial markets sharply down late Wednesday.

“In the short run, the effect is probably a recession. It’s going to raise the price of so many goods that can’t be made in the United States,” said economist Brad Setser of the Council on Foreign Relations. “In the long run, it’s a vision of the U.S. that is very isolated from the world.”

Jay Timmons, president of the National Association of Manufacturers, warned that his members operate on thin profit margins and cannot absorb the tariffs. Small businesses and restaurant owners issued statements decrying their added costs.

“This is catastrophic for American families,” said Matt Priest, president of the Footwear Retailers and Distributers of America.

The Gulf Coast shrimp industry, however, which has been battered by competition from countries such as India and Ecuador, welcomed the president’s move, saying it would “preserve American jobs.” And the steel industry said the tariffs would help it compete against foreign rivals that enjoy government subsidies.

The president’s long-awaited tariff plan is designed to spur a renaissance in domestic manufacturing and to fill government coffers with tax revenue, even as many economists warn that he is steering the U.S. economy toward slower growth and higher prices. While some on Wall Street continue to see the president’s aggressive trade stance as a negotiating ploy, one senior aide told reporters: “This is not a negotiation. This is a national emergency.”

After weeks of debate, Trump settled on a two-part trade overhaul strategy. All $3.3 trillion in annual imports will face a minimum tariff of 10 percent. Goods from roughly 60 countries that administration officials described as the “worst offenders” — including close allies like Japan and South Korea — will be hit with new taxes ranging from 10 percent to 50 percent.

Administration officials calculated individual tariff rates for each of those countries based upon an analysis of the trade practices that the White House found objectionable. The president described these tariffs as “reciprocal; that means they do it to us and we do it to them.”

In fact, the administration cut each country’s estimated figure in half and will levy what the president called a “discounted” rate.

“The president is lenient, and he wants to be kind to the world,” said one senior administration official who briefed reporters on the condition of anonymity.

The 10 percent baseline tax takes effect at 12:01 a.m. on April 5. The custom taxes hit on April 9.

The administration and its allies see the move as the start of an epic campaign to reverse more than three decades of ill-conceived economic policy and inaugurate a new “Golden Age.”

Trade liberalization deals like the 1994 North American Free Trade Agreement and China’s 2001 entry into the global trading system placed the working class in a “race to the bottom” with low-wage workers overseas, according to Trump officials.

As corporations moved their factories offshore, they and their Wall Street investors profited while blue-collar communities in the heartland suffered.

By imposing taxes on foreign goods, Trump hopes to encourage manufacturers to move their overseas factories to the United States. Critics say the president’s policies will help some industries while hurting others that rely on foreign parts.

“In the face of unrelenting economic warfare, the United States can no longer continue with a policy of unilateral economic surrender,” Trump said during a in the Rose Garden ceremony before an audience of guests, reporters and members of his Cabinet.

Wednesday’s one-two punch adds to a fusillade of new trade taxes the president has announced over the past 10 weeks on items such as steel and aluminum, copper, lumber and automobiles. The tax on foreign-made cars takes effect just past midnight on April 3.

As the president has amped up his attacks on U.S. trading partners, public opinion has swung against him. In a February Gallup poll, Americans by a margin of 81 percent to 14 percent called foreign trade more of an economic opportunity than a threat.

The president’s latest trade initiative represents a breathtaking political gamble. After returning to the White House on a wave of public anger over inflation, Trump is now asking voters to put up with a renewed period of rising prices in return for the distant promise of rebuilding domestic manufacturing.

Senior administration officials reject the inflation warnings, saying that Trump’s first-term tariffs produced no price shock. But the tariffs announced Wednesday affect more than five times as much economic activity, according to Erica York, an economist with the Tax Foundation, a center-right think tank.

Already, economists are warning that Trump’s tax increase on imported goods will mean sticker shock on some of Americans’ most important purchases, including smartphones, cars and homes.

The president and his aides blame the nation’s $1.2 trillion trade deficit on what they call “unfair” foreign trade barriers, including high tariffs, internal taxes and regulatory requirements. Many economists label those complaints exaggerated, saying the deficit stems from insufficient national savings.

The announcement is the culmination of weeks of internal discussions among senior Trump officials, who have tried resolving numerous conflicting purposes of the president’s tariff agenda.

Initially, Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent pitched the April 2 announcement as creating “reciprocal” tariffs, in which countries could negotiate to have their duties lowered in deals with the White House. But last week, Trump asked advisers why the administration could not impose a simple single flat tariff rate on all countries, perhaps as high as 20 percent, The Washington Post previously reported.

Having one flat tariff rate was also meant to provide an incentive for companies to invest in the United States that would not be later rescinded as part of a deal, an idea Trump had run on during his 2024 presidential campaign. This week, Trump officials sought to reconcile their push for a “reciprocal” tariff agenda with the president’s desire for a universal tariff, which could bring in hundreds of billions of revenue to federal coffers.

Meetings late Tuesday involved Bessent, Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick, Chief of Staff Susie Wiles and senior advisers Peter Navarro and Stephen Miller, according to two people familiar with the matter, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to reflect private deliberations. White House aides had grown concerned about the potential stock market reaction, said Wilbur Ross, who served as commerce secretary during Trump’s first term. That may explain why the administration did not pursue a 20 percent rate.

“There are some people who want it to be one rate for everywhere, on everything. Others want it everywhere, but by product. And others want it by product and by country. So there’s different ways of trying to accomplish it,” Ross said Wednesday before the official tariff announcement. “They’ve been scurrying around a lot at the last minute.”

In recent days, the administration dismissed increasing concern among investors, economists and some members of the Republican Party about the course Trump has chosen.

“They’re not going to be wrong. It is going to work. And the president has a brilliant team of advisers who have been studying these issues for decades,” White House press secretary Karoline Leavitt told reporters.

Americans are not convinced. In a CBS News-YouGov poll released Monday, 56 percent of adults surveyed opposed new taxes on foreign goods while 44 percent approved of them; 72 percent said they expected that tariffs would mean higher prices in the short term.

The president’s allies, meanwhile, see his economic overhaul in historic terms.

Trump’s goal is to “create an environment where we’re back to where we were before World War I,” said Newt Gingrich, former GOP House speaker. Trump believes the late 19th century was when “we were the strongest economy in the world, largely built around a high tariff, high wage, high manufacturing economy,” Gingrich said.

The current moment represents the “fifth great change in American history,” after the presidencies of Thomas Jefferson, Andrew Jackson, Abraham Lincoln and Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Gingrich said.

“There’s going to be turmoil; that’s a fact,” he said.