The U.S. labor market stumbled over the summer as job creation slowed sharply and previously reported figures were revised downward, raising fresh concerns about the momentum of the economic recovery amid rising trade tensions and policy uncertainty.

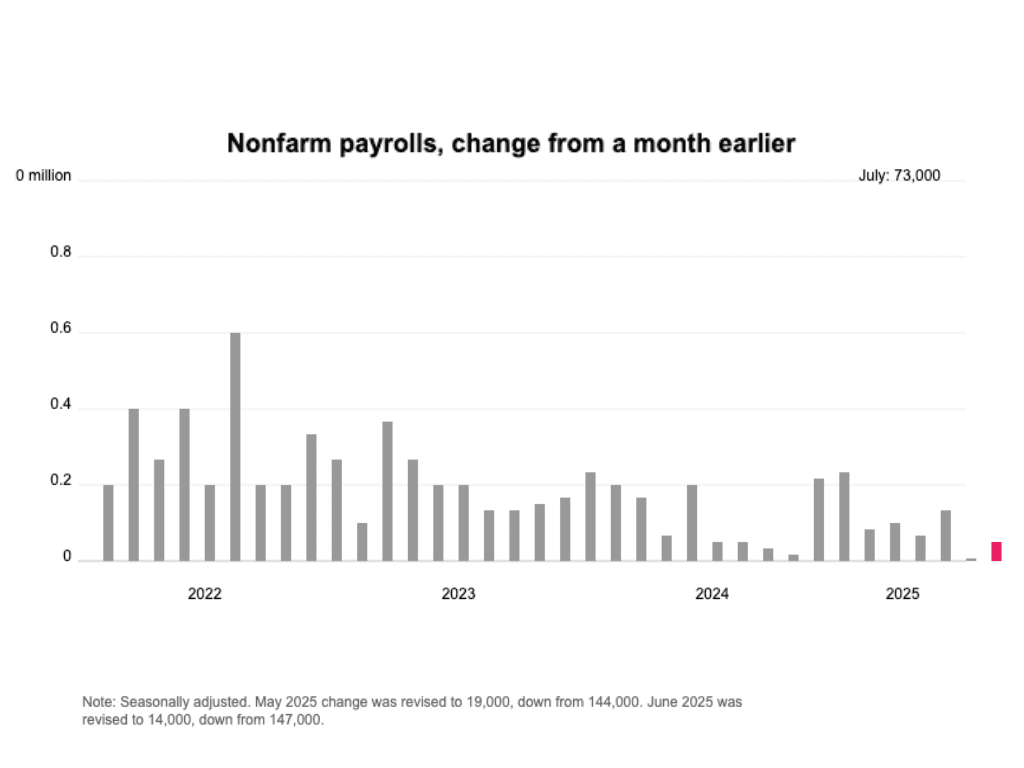

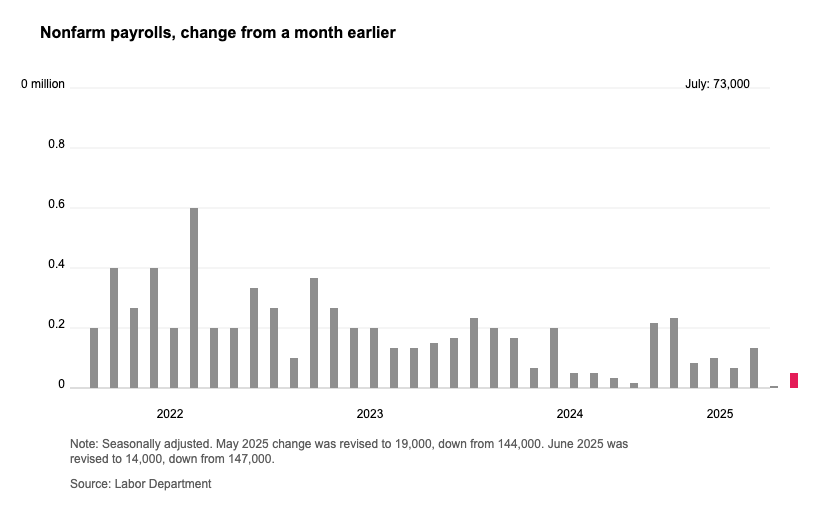

According to the Labor Department’s latest employment report released Friday, nonfarm payrolls increased by just 73,000 in July, a figure well below economist forecasts and the weakest showing since January. Compounding the disappointment, the job numbers for May and June were drastically revised—May’s gain was slashed from 144,000 to 19,000, and June’s from 147,000 to 14,000.

The three-month average gain now stands significantly below the 150,000 threshold, a sign of a cooling labor market. July’s job growth also fell short of the median estimate of 110,000 in a Reuters survey, where forecasts ranged from no change to 176,000 new jobs.

Unemployment Rate Rises as Tariff Uncertainty Bites

The unemployment rate edged back up to 4.2% in July from 4.1% in June, still within the narrow 4.0%–4.2% range prevailing since mid-2024. However, economists warned that the figure masks deeper structural issues, including a shrinking labor force due to immigration curbs and accelerating baby boomer retirements.

“We’re seeing growing anecdotal and survey evidence that employers have tapped the brakes on hiring,” said Stephen Stanley, chief U.S. economist at Santander U.S. Capital Markets. “There’s policy uncertainty everywhere—tariffs, immigration, education spending, government layoffs—and it’s chilling business planning.”

The July slowdown follows a temporary hiring surge in June, largely attributed to a seasonal spike in state and local education employment. Economists now view that bump as a one-off anomaly that masked the broader slowdown in hiring.

Tariffs and Fed Policy Cast Shadows

The labor market report comes on the heels of a flurry of trade moves from President Donald Trump. On Thursday, the administration imposed steep tariffs on dozens of trading partners, including a 35% duty on many Canadian goods, just ahead of a Friday trade deal deadline. This escalation has stoked inflation fears and increased business uncertainty.

“The tariffs are now starting to bite into both margins and long-term planning,” said Michael Reid, senior U.S. economist at RBC Capital Markets. “Until firms know their cost structure, they’re hesitant to expand.”

Meanwhile, the Federal Reserve left its benchmark rate unchanged at 4.25%–4.50% on Wednesday and signaled a cautious tone on future policy moves. Fed Chair Jerome Powell acknowledged “downside risks” in the labor market but offered no hints of a near-term rate cut.

“The July jobs report is unlikely to shake the Fed out of its ‘wait-and-see’ posture,” said Gregory Daco, chief economist at EY-Parthenon. “But it will add further evidence that the labor market is gradually losing momentum.”

Financial markets, which had been pricing in a potential rate cut in September, have now pushed expectations to October or later, especially with inflation heating up from rising import costs. However, some analysts say the Fed could still be forced to act if upcoming data—including September’s payrolls benchmark revisions—reveal deeper labor market cracks.

“If it’s an ugly downward revision, the Fed will move—there is no question,” said Brian Bethune, an economics professor at Boston College.

The slowdown in job growth also arrives at a politically sensitive moment. With the 2026 midterm campaign season looming, both parties are expected to weaponize the data. Republicans are expected to double down on tariffs and “America First” rhetoric, while Democrats may lean into social safety nets and wage support.

Though not yet a labor recession, the data reflect a marked deceleration in hiring and economic activity. Businesses are navigating uncharted waters—supply chain volatility, tariff unpredictability, and geopolitical tensions—while the Fed remains on pause.

For now, job growth of 100,000 or less may be enough to maintain labor market equilibrium, given tighter immigration flows and demographic headwinds. But that lower “breakeven” threshold is little comfort to workers or businesses hoping for a rebound.

“This is not a collapse,” said Stanley. “But it’s a slowdown with no clear end in sight.”