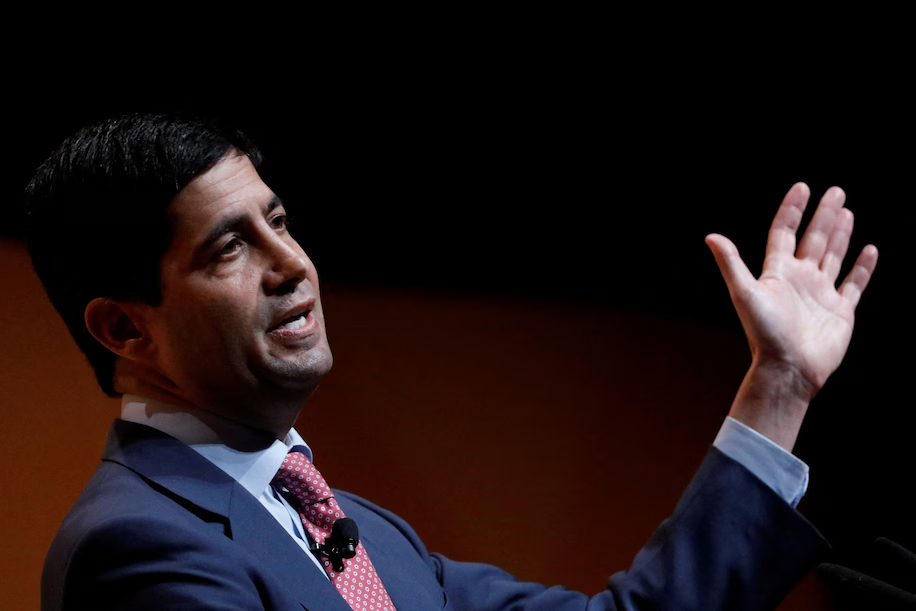

Kevin Warsh was sitting in the East Room of the White House when President Donald Trump took a beat to praise the former central banker. At the January 2020 signing ceremony, Trump turned to the former Federal Reserve governor — a finalist for the central bank’s top job a couple of years earlier — and delivered an unscripted aside.

“I would have been very happy with you,” Trump said, singling out Warsh. “I could have used you a little bit here. Why weren’t you more forceful when you wanted that job?”

It was yet another implicit swipe at Jerome H. Powell, the Fed chair Trump had ultimately selected in late 2017 but soon soured on — and a revealing moment for Warsh, whose close ties to Republican economic circles have long kept him in the conversation for top policymaking roles.

Now, with about a year remaining of Powell’s term as chair, Warsh is once again seen as a leading contender to run the central bank. The banker had previously served on the seven-member Fed board from 2006 to 2011, becoming, at 35, the youngest governor in its history.

Warsh has long been viewed by Wall Street as a strong contender to succeed Powell, whose policies he has criticized. Warsh was also briefly under consideration to become Trump’s compromise pick to run the Treasury Department amid infighting for the job between Wall Street financier Scott Bessent and brokerage executive Howard Lutnick last fall. Bessent, who ultimately became treasury secretary, told Bloomberg last month that White House officials will start interviewing for the Fed job later this fall.

If nominated, Warsh could face questions about his long-standing, hawkish views over inflation and the significant expansion of the Fed’s balance sheet. He has argued that the Fed’s extended reliance on low interest rates and large-scale asset purchases has blurred the line between monetary and fiscal policy, encouraging unsustainable levels of government spending. That view could put him at odds with a White House eager to spur faster growth and looser monetary policy to juice the economy.

Still, some Fed watchers see Warsh as a more plausible option compared with some of the people Trump considered for the central bank during his first term. Economics commentator Judy Shelton and the late Herman Cain — a former GOP presidential candidate and restaurant executive — failed to get on the Fed board when it was clear a significant number of Republican senators wouldn’t support them. Cain wasn’t even nominated.

Others expected to be in the mix include Kevin Hassett, who heads the White House National Economic Council, and Bessent, a former hedge-fund executive. Fed governor Christopher Waller is also seen by Fed watchers as a possible pick.

Warsh has been out of government for nearly 15 years, some critics said, which could put him at a disadvantage with other officials vying to succeed Powell. Neil Dutta of Renaissance Macro Research noted that Powell and his immediate predecessors, Janet L. Yellen and Ben S. Bernanke, were elevated to the top job from senior roles within the central bank.

“He hasn’t been anywhere close to making decisions on matters of monetary policy in a long time. All he does is criticize decisions after they are made,” Dutta said.

White House spokesman Kush Desai said any discussion about potential personnel and nomination decisions that have not been officially announced by the White House is “pure speculation.”

Trump has said he doesn’t intend to fire Powell, despite repeatedly criticizing the Fed leader for not lowering interest rates to soften the effects of his disruptive trade policies. Still, it’s unclear when Trump will actually be able to replace Powell. His term as chair runs until May 2026, but he can stay on the Fed’s board as a governor until January 2028. Powell hasn’t said whether he’ll step down immediately once his term as chair ends. The earliest chance Trump has to install a new Fed governor may not come until January, when Adriana Kugler’s term expires.

Warsh began his career in 1995 at Morgan Stanley, where he worked as a mergers and acquisitions banker. He joined the George W. Bush administration in 2002 as an economic adviser, and four years later was appointed to the Fed. There, he served as a liaison between the central bank and Wall Street during the 2008 financial crisis, before stepping down in 2011.

In a speech last week on the sidelines of the spring meetings of the International Monetary Fund and World Bank in Washington, Warsh criticized the Fed for “systematic errors” that allowed inflation to surge coming out of the pandemic. The Fed’s inability to control inflation, along with what he described as its efforts to cater to political issues such as climate change, had contributed to the challenges to its independence from the president.

“The Fed’s current wounds are largely self-inflicted,” Warsh said at an event hosted by the Group of Thirty, an independent global body that includes prominent economic leaders and policymakers. He characterized his lecture as a “love letter” to the Fed but said its officials should be subjected to “serious questioning, strong oversight, and, when they err, opprobrium.”

Warsh said that the Fed should narrow its focus but could have been more outspoken about the risks of large federal deficits, which he blamed the central bank for helping to facilitate through the growth of its balance sheet since the 2008 financial crisis.

He said he supported the Fed’s initial bond-buying stimulus push — helping to pull the economy out of a sharp, crisis-triggered downturn — but he took issue with the Fed continuing those efforts in the years after the crisis.

Congress found it considerably easier appropriating money knowing that the government’s financing costs were effectively subsidized by the central bank, Warsh said. Other Fed watchers say the lackluster economic recovery, featuring high unemployment and below-target inflation, necessitated looser monetary policy for longer.

Warsh is married to Estée Lauder heiress Jane Lauder. Since leaving the Fed, he has been a lecturer at the Stanford Graduate School of Business, a scholar at the conservative Hoover Institution and a business partner of investor Stanley Druckenmiller.

Warsh’s ties to Republican circles are extensive. His father-in-law, billionaire cosmetic heir Ronald Lauder, is also a Trump ally who first floated the idea of the United States buying Greenland during the first term.