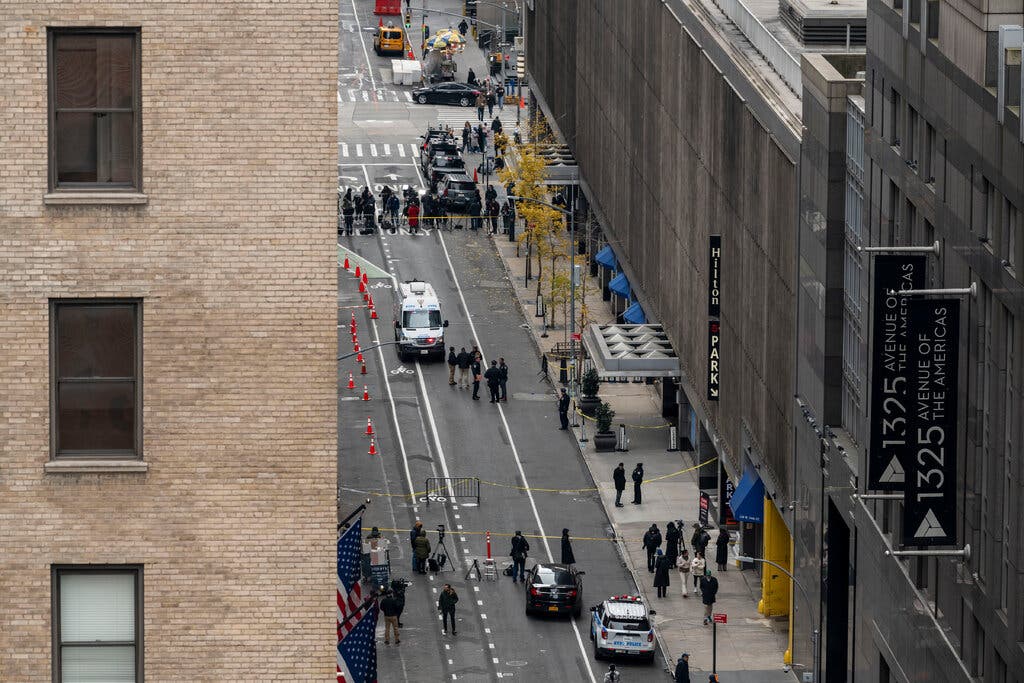

By Lola Fadulu and Callie Holtermann | Dec 10, 2024 Updated

The killing of the UnitedHealthcare chief executive Brian Thompson has mesmerized a deeply polarized nation that shares a collective frustration over dealings with health insurance companies.

On social media, some people have cheered for the gunman and expressed little remorse over the death of Mr. Thompson, 50, a father of two boys from Maple Grove, Minn., with some painting him as the villain in a national health care crisis.

And now that the identity of the suspect, Luigi Mangione, 26, has been revealed and more photos of him have emerged, he is being defended or even applauded in some circles.

That adulation reflects public anger over health care, said Nsikan Akpan, managing editor for Think Global Health, a publication that explores health issues at the Council on Foreign Relations. “The UHC killing and the social media response stem from people feeling helpless over health coverage and income inequality,” he said. The topic is so often ignored by American public officials, he said, that voters have stopped listing it as a top priority.

“A targeted killing won’t solve those problems, and neither will condoning it,” he added.

Experts who reviewed the flood of social media posts expressing support for Mr. Mangione said that while it can be difficult to assess the provenance of posts, none have the telltale signs of an “influence campaign” by a foreign entity.

“People are legitimately actually pissed off at the health care industry, and there is some kind of support for vigilante justice,” said Tim Weninger, a computer science professor at Notre Dame and expert in social media and artificial intelligence. “It’s organic.”

Along with the more shocking posts online that have supported Mr. Mangione, numerous comments expressed anger at the murder of a man who spent years rising through the ranks of corporate America.

In recent months, Mr. Mangione had become estranged from family and friends, some of whom worried about his mental health when he fell out of touch after having spinal surgery, some of his friends said.

No evidence has yet emerged that he had a specific grievance with care provided by UnitedHealthcare or its parent company, UnitedHealth Group. In a short manifesto recovered from his backpack, he criticized United as “too powerful” and as abusing “our country for immense profit” but does not mention any of his own interactions with the company, or if he was enrolled in its coverage.

But as Mr. Mangione was led to an extradition hearing in Pennsylvania Tuesday, he seemed to nod to the outrage brewing in America, shouting to media gathered nearby, “This is completely out of touch and an insult to the intelligence of the American people.”

Mr. Mangione’s document tracks in part with the outrage that many Americans feel. As UnitedHealthcare’s market capitalization has grown, he wrote, American life expectancy has not. His writings also condemn companies that “continue to abuse our country for immense profit because the American public has allowed them to get away with it.”

“These parasites had it coming,” read the manifesto. It added: “I do apologize for any strife and trauma, but it had to be done.”

The anger over the U.S. health care system has long been explored in popular culture.

In “John Q,” Denzel Washington plays a man whose son needs a heart transplant but whose insurance won’t cover it. In the slasher movie “Saw,” the killer targets the man who denied him insurance coverage for an experimental cancer treatment. A chemistry teacher named Walter White starts cooking methamphetamine to pay his medical bills in the series “Breaking Bad.”

Hollywood and the publishing industry reflect reality for many Americans: While insurance companies cover millions of claims a year, their denials can seem unjust.

That sentiment has grown in recent years, health insurance executives, policy experts and pollsters say, fueled by the rising costs of medical care and the emergence of huge bureaucracies that make seeing the doctor more difficult.

“There is this rage that is coming out,” said Michael Perry, a pollster who has conducted hundreds of health care focus groups over the past decade. A few years ago, he would hear mixed consumer views on health insurance, with wealthier people generally speaking favorably about their plans.

“I don’t hear that anymore,” he said. “The wealth gap has closed, and there is no amount of money that can buy you good insurance.”

High deductibles and co-payments are causing nearly two of five working-age adults to delay visiting the doctor and filling prescriptions, according to an August study by the Commonwealth Fund, a nonprofit, bipartisan health care research foundation. Those who do get care can become burdened by medical or dental debt, something almost one-third of working-age adults report experiencing, the study said.

“Once people get sick and need to use their plans, things can start to go wrong,” said Sara Collins, a senior scholar at the Commonwealth Fund who focuses on access to health care coverage. “When that happens to people, they really aren’t sure what to do.”

Many patients don’t realize they have the right to challenge an erroneous bill or a denial of coverage, she said. Others say they don’t have time to navigate the labyrinthine insurance system to do so. The privileged pay up, and the poor give up.

“What we’ve ended up with is a deeply frustrated population with few channels for equitable relief,” said Warris Bokhari, who left his vice president job at the insurer Anthem in 2021 and has since started a new company that helps patients file appeals. “No one is condoning violence against executives, but there are private tragedies happening every single day. For the most part, they go totally unheard and unknown.”

Meanwhile, health insurance companies are profiting. The division overseen by Mr. Thompson reported $281 billion in revenue last year and provided coverage to more than 50 million Americans via plans for individuals, employers and people in government programs like Medicare.

Mr. Thompson earned a total compensation package last year of $10.2 million.

The fury over the high levels of pay for executives of an industry that so many resent was clear online in recent days. An internet meme circulating showed an image of a Patagonia vest, a wardrobe item that is popular with chief executives, flying at half-staff in mock sympathy for Mr. Thompson.

On social media, some posts are openly rooting for Mr. Mangione, an Ivy League graduate who was valedictorian of his private high school class and who comes from an influential real estate family in the Baltimore area.

Commenters swooned over his looks; “Dave Franco” was trending on the social media platform X on Monday night, with users suggesting the actor play Mr. Mangione in a movie about the murder. “Free Luigi” T-shirts were offered for sale. A crypto coin was named after him and initially soared in value. A post that photoshopped Mr. Mangione into a scene in Tulsa, Okla., on the day of the shooting aimed to give him an alibi.

The posts and commentary celebrating a murder suspect are crass yet not particularly unfamiliar in a country that has sometimes celebrated frontier justice and revenge killings.

“There’s a long, long history of vigilantism in the United States dating to pre-Revolutionary times of people taking the law into their own hands because they don’t think they can get justice any other way,” said Michael Asimow, a professor at Santa Clara University School of Law.

Mr. Mangione has won support by taking action against what seems to be an intractable problem, he said — even though he is accused of committing murder.

“Just about everybody has had negative experiences with health insurance companies that don’t pay the claims or pay very low amounts,” Mr. Asimow said, “so it’s not surprising at all.”

Be First to Comment