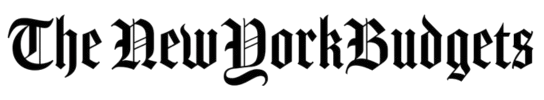

Xavier Becerra, who has led the Department of Health and Human Services, says federal agencies are outmatched in a world of “instantaneous information and disinformation.”

By Mark Ericson | Jan 13, 2025 at 09:06 a.m. ET Updated | U.S. NEWS & Politics

As they entered office at the height of the coronavirus pandemic in early 2021, Xavier Becerra and his allies had a plan to restore Americans’ faith in the nation’s beleaguered public health agencies.

Becerra, tapped by President Joe Biden to lead the Department of Health and Human Services, empowered career government scientists and experts muzzled under the Trump administration. Biden officials took on social media posts they said spread disinformation about coronavirus vaccines, urging Facebook and other companies to remove them. The White House mounted a nationwide vaccination campaign, convinced the results would win over skeptics.

Four years later, the pandemic has receded. But trust in America’s health agencies has not recovered. The percentage of adults who regarded the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as “excellent” or “good” fell from 64 percent in April 2019 to 40 percent in October 2021 — a rating that has stubbornly refused to budge in the subsequent three years, according to Gallup polls, despite the Biden administration’s efforts to rebuild confidence. Other surveys found similar declines in trust and approval for federal health agencies, and the people who lead them, driven by GOP skepticism.

Sitting in his office at HHS headquarters, America’s top health official identified a culprit: a media climate that he says drowns out reliable information. False claims about vaccines run rampant online; government health experts at news conferences barely make a dent compared with influencers who have huge followings.

“I can’t go toe to toe with social media,” Becerra said in a wide-ranging interview Wednesday, arguing that even a Cabinet secretary can be hemmed in. As examples, Becerra cited the lawsuits the Biden administration faced after urging social media companies to take down posts the White House considered disinformation. And he noted that officials can’t formally disclose many details about negotiations to lower prescription drug prices. “I don’t get to write whatever I want,” he said.

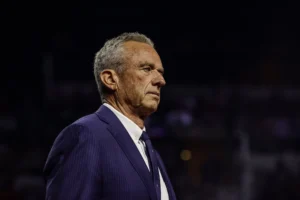

The health secretary never mentioned Robert F. Kennedy Jr., but the longtime anti-vaccine activist’s shadow hung over Becerra’s answers. President-elect Donald Trump’s pick to run HHS has relentlessly criticized the agencies he soon may lead, amplified false claims about vaccines and offered alternatives to what he called government misinformation. Now, Kennedy, who has said he is not anti-vaccine, could occupy the office where Becerra was giving his exit interview.

If Kennedy is confirmed by the Senate, he will be the first HHS secretary whose personal celebrity arguably eclipses the agencies he oversees. The scion of the Democratic political dynasty has 4.5 million Instagram followers — more than HHS (about 200,000 followers) and its subagencies combined. His bid for the presidency won him millions of supporters, some of whom said they agreed with Kennedy’s “Make America Healthy Again” agenda.

The low-profile Becerra, meanwhile, remains largely anonymous to the regular American. (As Becerra stood in the airport on one trip last year, shadowed by a Washington Post reporter, hundreds of travelers walked past, and not one approached the man 12th in line of succession to the presidency.) Some of that stems from his cautious approach to media; even in his exit interview, he steered clear of complaints about the incoming Trump administration.

“I want to be careful. I’m not going to try to speak for the next administration. I’m not going to try to characterize what any potential nominee is saying or critique it, because that’s not my place,” Becerra said.

Instead, he focused his answers on his sprawling department, a portfolio that touches everything from Americans’ food and drugs to the nation’s crisis response. Down the hall, in a secure room known as the Secretary’s Operations Center, emergency personnel monitored the fires raging in Southern California. Other HHS staffers were helping support arrangements related to former president Jimmy Carter’s viewing in the Capitol or preparations to guard against the threat of avian flu.

But the hulking HHS headquarters was mostly quiet last week, with Washington tamped down by snow and the federal government shuttered Thursday for Carter’s funeral — a muted ending to four years marked, in many ways, by achievements that Becerra promised senators when he asked for their votes to confirm him.

The Biden administration helped administer hundreds of millions of coronavirus vaccine shots. It oversaw record-high enrollment through the Affordable Care Act (ACA). It rolled out new initiatives decades in the making to lower drug prices.

But the bundle of health policies wasn’t enough to sway the electorate, and each achievement had a flip side.

The coronavirus vaccines saved lives — but the Biden administration’s vaccine mandates helped spark a lingering backlash against health agencies. The rate of uninsured Americans fell to an all-time low, but experts have focused on the nation’s relatively poor health outcomes, saying coverage does not guarantee access to care. The drug-price victories were hard to explain to voters, and it is not clear whether Trump and congressional Republicans will seek to unwind the federal law that empowered Medicare to negotiate directly with drug companies — although Becerra, a former California attorney general, said he would fight to protect it.

“I’m not AG anymore, but I’d be ready to sue them,” he vowed.

Surviving backlash

Becerra, who was a congressman for more than two decades before becoming California’s top lawyer in 2017 and then the nation’s health secretary in 2021, is a veteran of Washington battles.

Some of the more recent fights concerned his own job: The Post and other outlets reported on internal frustrations with Becerra’s leadership during the pandemic and his agency’s response to unaccompanied children at the border. Some officials mused about replacing him with someone they said would be more proactive.

Becerra acknowledged the learning curve when taking charge of HHS, which oversees programs such as Medicare and Medicaid; approves drugs, medical devices and vaccines; regulates hospitals, physicians and other health-care providers; and steers many other initiatives affecting food and medicine. It also plays a central role in the nation’s human services, such as caring for unaccompanied migrant children.

“I didn’t realize how vast this agency’s jurisdiction is,” Becerra said, reflecting on how HHS found itself at the center of various crises, such as a 2022 baby formula shortage. “Since when has HHS been the administrator and distributor of infant formula?”

He said he quieted the criticism by demonstrating results, including smoothing the process of HHS taking custody of unaccompanied migrant children.

“We proved that we could execute,” Becerra said.

One area of execution: ACA enrollment, with Becerra’s team announcing last week that nearly 24 million Americans are covered through the program. Millions of those enrollees benefit from subsidies expanded by the Biden administration, which are set to expire at the end of this year. Democrats introduced legislation last week to extend those subsidies, even as Republicans look to end them, saying they distort the purpose of the ACA by subsidizing Americans who don’t need the assistance. The disagreement threatens to tee up a major political fight.

“We have strengthened the subsidy support that Americans get that have made these plans extremely affordable,” Becerra said. “I think we’ve convinced a lot of Americans that this really is the best deal in town.”

Becerra also touted the Biden administration’s work on capping out-of-pocket costs at $2,000 a year for covered prescription drugs for Medicare Part D enrollees; a decline in drug overdose and suicide deaths; and the launch of the 988 crisis hotline.

He declined to comment on his next steps after leaving government later this month, although allies widely expect him to run for California governor.

Rebuilding trust

Becerra acknowledged that his team struggled to win back the support of skeptical Americans, who he said are being bombarded by “instantaneous information and disinformation” on social media.

The health secretary contended that the government is outmatched, suggesting that Congress should set aside more resources for his nearly $2 trillion agency.

“I don’t have a budget that Pfizer has to do marketing and advertising,” Becerra said, invoking the pharma giant that spends billions of dollars to promote its drugs. “Will [Congress] give me some money to compete out there with all the disinformation?”

He also defended Biden administration efforts that Kennedy and others have criticized as heavy-handed, such as requiring federal workers and federal contractors to be vaccinated.

“Every chance I have to do what the science and the evidence is telling me is going to protect Americans and save lives … I’d do it again,” Becerra said.

Social media companies, after working closely with the Biden administration during the pandemic, have offered their own rebukes of government. Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg told popular podcaster Joe Rogan last week that he disagreed with the Biden administration’s push to take down social media posts critical of coronavirus vaccines, and has said he regretted complying with the White House’s requests.

The flagging support for federal health agencies may shift with a change of administration. Just 19 percent of Republicans gave the CDC high marks in September, down from 71 percent in April 2019, according to Gallup surveys. Support for federal agencies often correlates with partisan politics, with GOP voters more willing to view agencies positively when a Republican president is in office, pollsters have said.

Becerra said the difficulties his team faced reflect a deep distrust of institutions.

“Do I think the American public has come back to a point where they trust, whether it’s the ACA or vaccines, as much as they trust their priest or their rabbi? No,” Becerra said. “But then again, I don’t think priests … have the same standing they used to have before, either.”

The health secretary wound down his interview with a frank plea about how public health experts can better reach Americans.

“I don’t know what more we can do,” Becerra said. “I’m more than willing to listen if somebody’s got some great ideas.”