By Huber Jafirson | Jan 08, 2025 at 02:20 a.m. ET Updated

Decades after investigators unearthed thousands of human bones and bone fragments on a suspected Indiana serial killer’s property, a renewed quest is playing out in laboratories to solve a long-running mystery: Who were they?

A new team working to identify the unknown dead says the key to their success will be getting relatives of men who vanished between the mid-1980s and the mid-1990s to provide samples of their own DNA.

Those samples can then be screened against DNA profiles scientists are extracting from the remains, which were found starting in 1996 on Herbert Baumeister’s sprawling suburban Indianapolis property.

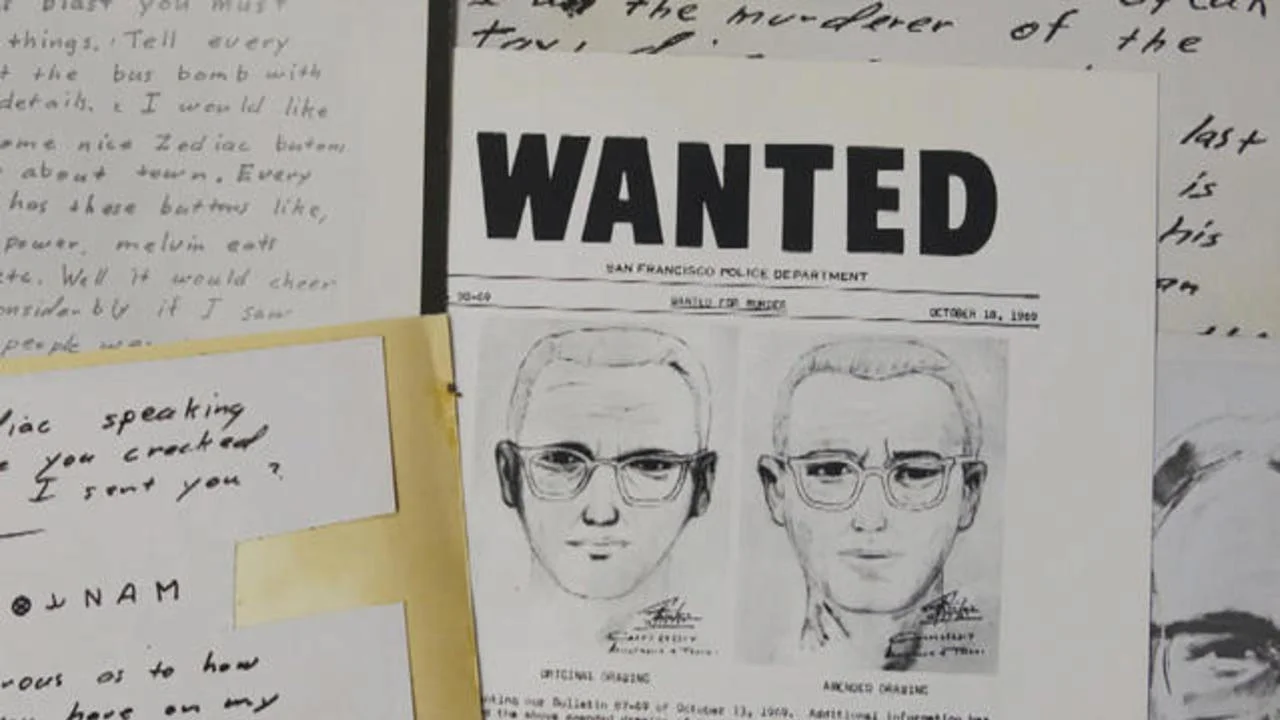

The original investigators believed that at least 25 people were buried at Baumeister’s 18-acre Fox Hollow Farm estate in Westfield, based on evidence that included 10,000 bones and bone fragments, as well as handcuffs and shotgun shells.

Baumeister, a 49-year-old thrift store owner and married father of three, killed himself in Canada in July 1996 before police could question him, taking with him many secrets, including the names of his presumed victims.

Investigators believed that while his family was away on trips, Baumeister, who frequented gay bars in Indianapolis, lured men to his home, where he killed and buried them.

By the late 1990s, authorities had identified eight men using dental records and available DNA technologies. But then those efforts stopped, although the remains of at least 17 people may have still been unidentified.

Hamilton County Coroner Jeff Jellison said the renewed identification effort revealed that county officials at the time decided not to fund additional DNA testing, which “essentially halted further efforts to identify the victims and placed the cost of a homicide investigation on family members of missing people.”

“I can’t speak for those investigators, but it was just game over,” Jellison said.

An unfinished job

As decades slipped by, the bones and fragments sat in boxes at the University of Indianapolis’ Human Identification Center, whose staff helped excavate the remains.

That changed after Eric Pranger sent Jellison a Facebook message in late 2022. The Indianapolis man’s family had long believed his older cousin, Allen Livingston, was among Baumeister’s victims. According to the Doe Network, Livingston disappeared on the same day as Resendez.

Livingston was 27 when he vanished in August 1993 after getting into someone else’s car in downtown Indianapolis. After hearing about Baumeister three years later, his mother, Sharon Livingston, and other relatives began suspecting that Allen, who was bisexual, was among the dead.

Jellison was about to take office when Pranger asked if he could help get some answers for his aunt, who had serious health problems.

“How do you say to no to that? That’s our job as coroners by statute, to identify the deceased,” Jellison said.

In late 2022, police took DNA samples from Sharon Livingston and one of her daughters. Jellison began working with a team that includes the Indiana State Police, the FBI, the Human Identification Center, local law enforcement and a private company that specializes in forensic genetic genealogy.

A family finds some closure

Staff at the Human Identification Center, where the remains are stored in a temperature- and humidity-controlled space, selected some of the most promising bones for DNA analysis.

At the Indiana State Police Laboratory, scientists cut out sections of bone, froze them with liquid nitrogen and pulverized them into a fine powder. They then used heat and chemicals to break open bone cells in the first step toward extracting a full DNA profile.

Nearly a year after hearing from Pranger, Jellison announced in October 2023 that a ninth Baumeister victim had been identified: Allen Livingston.

Sharon Livingston finally received some form of closure. She died in November 2024.

“It made me happy to be able to do this for my aunt,” Pranger, 34, said. “I’m the one who got the ball rolling to bring her son home after 30 years and I felt privileged.”

“After Allen was identified I was so excited and then after the fact I asked myself, ‘Now what? I got answers, but what about all the other families?'” Pranger added.

The other victims

Jellison said about 40 DNA samples have been submitted by people who believe a missing male relative may have been killed by Baumeister. He said those are entered into the FBI’s Combined DNA Index System, or CODIS, but are used solely for identifying missing people.

The coroner and his partners hope to get more DNA samples from relatives of men from across the U.S. who vanished between the mid-1980s and mid-1990s. They noted the men may have been traveling and stopped in Indianapolis to visit friends or sample its nightlife.

To date, scientists have extracted eight unique DNA profiles — all male — from more than 70 of the 100 bones that were sent to the Indiana State Police Laboratory by Dr. Krista Latham, the Human Identification Center’s director.

One matched DNA samples provided by Livingston’s mother and sister. Four matched four of the eight men first identified in the 1990s: Jeffrey Jones, Manuel Resendez, Johnny Bayer and Richard Hamilton.

The three other DNA profiles remain unidentified and two are still undergoing testing. Those three have boosted Baumeister’s presumed victims to 12.

“Unusual spot to find bodies”

CBS affiliate WTTV reported the case began in June 1996 when Baumeister’s 15-year-old son discovered a human skull about 60 yards away from the home.

The investigation began while Baumeister and his wife of 24 years were in the middle of divorce proceedings, WTTV reported. The day after their son found the bones, Baumeister’s wife was granted an emergency protective order and custody to keep him away from her and the three children.

At the time, Baumeister explained away the discovery, saying it was part of his late father’s medical practice, the station reported.

Three days after the boy discovered the remains, more remains were found by Hamilton County firefighters, perplexing investigators, the station reported.

“It’s an unusual spot to find bodies,” then-Sheriff Joe Cook is quoted as telling The Indianapolis Star.

What’s next?

Jellison and his partners say their identification effort could take several more years to complete.

Most of the bones were crushed and burned, reducing their potential to yield usable DNA. Latham, a professor of biology and anthropology, said bone fragments deemed in poor shape are being held back from the destructive testing process in hope that future DNA technologies can unlock their secrets.

She noted some of the men may have been estranged from relatives or ostracized because of their sexuality. No one may have noticed when they vanished.

“These are individuals who were marginalized in life. And we just need to make sure that that’s not continuing in death as well,” Latham said.

For the ongoing work, Jellison has obtained DNA reference samples from relatives of seven of the eight men originally identified in the 1990s. The eighth man, Steven Hale, was adopted and efforts to locate biological relatives have thus far failed, the coroner said.

Relatives of missing men who want to provide family DNA reference samples for the effort to identify remains can contact the Indiana State Police missing persons hotline at 833-466-2653 or the Hamilton County Coroner’s Office at 317-770-4415.

As remains are identified, piece by piece, families can opt to have them cremated and interred at a memorial dedicated in August in Westfield. It includes a plaque with the names of the nine identified victims, with room for more names.

Linda Znachko, whose nonprofit, Indianapolis-based ministry He Knows Your Name, paid for the monument, said at the memorial’s dedication that the identification campaign “will bring honor to those who lost their lives at the Fox Hollow tragedy.” Remains belonging to Livingston and Jeffrey Jones were added to the memorial’s ossuary and white doves were released during the dedication.

Livingston’s younger sister, Shannon Doughty, attended with several relatives, including Pranger. She said it was a relief finally knowing what happened to her brother, despite his tragic end.

“At least you know,” said Doughty, 46. “The fear of the unknown is the worst, right? So just knowing, it’s a multitude of emotions. You wanted to know but you didn’t want to know. But you needed to know.”